Exploiting string format vulnerabilities

During a lab of Software Security class at EPFL, we came across this exercise on

which I pulled my hairs out. It is about exploiting a vulnerability coming from

the string format parsing algorithm with an unsafe function such as printf.

The problem

The problem is posed with the following C program:

// credits to https://hexhive.epfl.ch/

// compile with `gcc -static -O0 -m32 -s -Wl,--section-start=.text=0x11111111 2.c`

// note that -m32 is so addresses are short and --section-start is so there's no NULL in the address

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

// this leaks memory but whatever, the program will exit quickly

char* read_flag(void) {

FILE* f = fopen("flag", "r");

char* flag = calloc(128, sizeof(char));

fscanf(f, "%127s", flag);

fclose(f);

return flag;

}

char* flag;

int main() {

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

flag = read_flag();

char input[128];

int n = 42;

printf("%d\n", n);

printf("Hmmm look at this interesting pointer: %p\n", flag);

printf("%d\n", n);

fflush(stdout);

printf("Input your magical spell! ");

scanf("%127[^\n]", input);

printf(input);

printf("\nHope you got what you wanted!\n");

fflush(stdout);

return 0;

}

Let us say this program is compiled and the executable runs on a server that we

can reach. Our goal is to display the content of the file ./flag, and we

can observe that fortunately, this one is loaded in the variable flag (with

flag=read_flag();), but the content of this variable is not printed :(.

Our attack surface

Getting back to the theory, we observe that this simple program does 2 things:

- Gives us the value of the pointer

flag, aka, the address for the first char of a string containing the flag value we want to retrieve. - Reads our input and stores it in the character array pointed to by the

input, and prints it immediately withprintffunction.

Although we immediately observe that the usage of printf on unsanitised input

is theoretically insecure, exploiting it is another story, but we are off a

great start.

String format allows doing WHAT?

The key thing to understand is that string format hide some tricky tricks in

their implementation. Namely, understanding the behaviour of the printf

algorithm will let us understand how to make our exploit.

First, to get this, I extensively used this blog

post

that I really recommend reading for more details about what will follow. I will

assume the reader know the basics of normal use for the printf function with

format specifier.

What we will be interested in now is notably the %p format specifier. Here’s a

sample program to explain our point:

a_pointer int*

printf("%p", a_pointer)

This prints the address of the value pointed to by a_pointer, namely, and

address in memory (e.g, 0x56550090). To do so, printf basically follows the

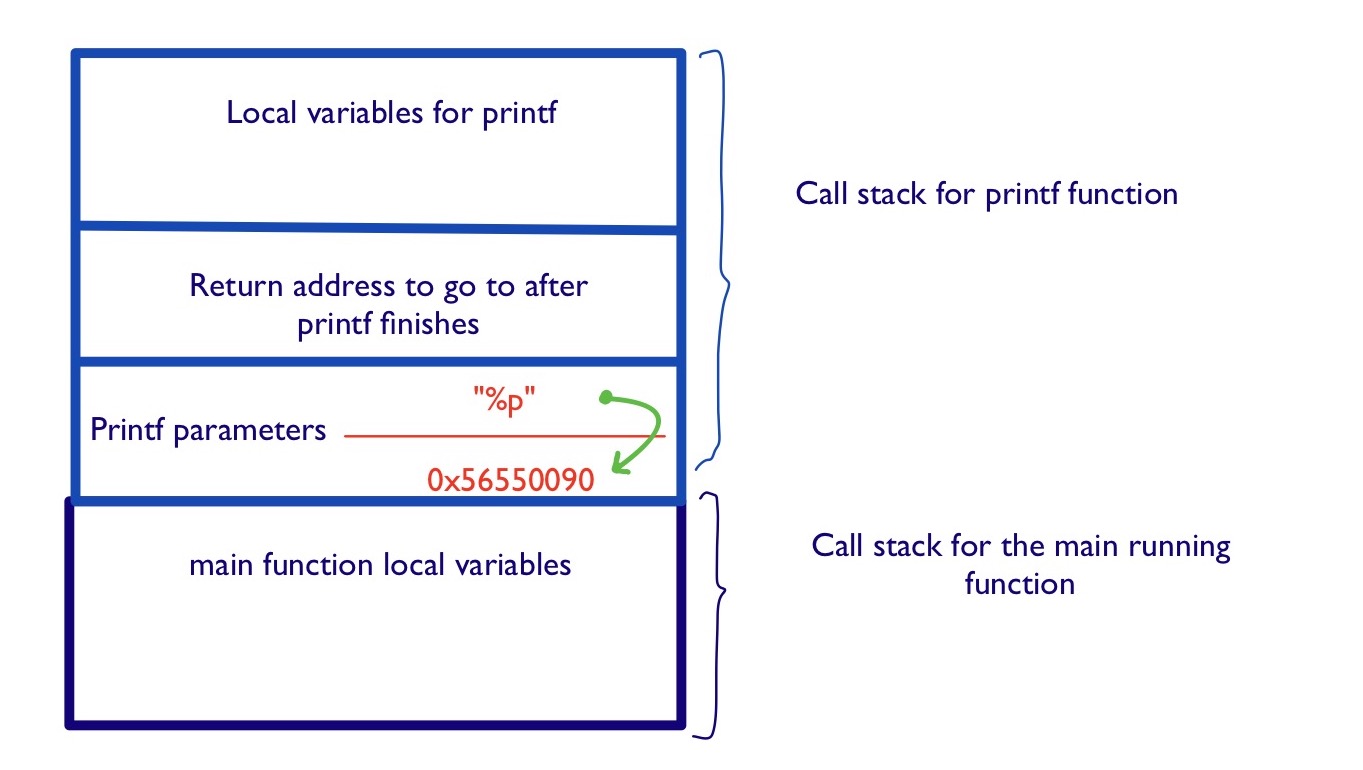

calling convention of functions in C. When the printf function is called, our program does the following:

- It pushes the function’s parameters on the stack

- It also pushes the return address on the stack

- It pushes eventually other variables (registers values to be reused, frame information, …) that we are not interested in today

- It allocates space for the local variables used by

printfthe function.

This image from the Call stack Wikipedia page gives a good idea for this.

The image above represents roughly the state of the stack when the function is

called. We see that the stack stores 2 parameters for the printf function: a

pointer to the "%p" format string, and the example value of the a_pointer

variable (0x56550090).

In a simplified version, the printf algorithm reads the string pointed to

by the first parameter, and if it meets a special format specifier (such as

%p), it advances a pointer, represented by the green arrow, that gets the

next parameter and uses it as a replacement for the format specifier when

printing.

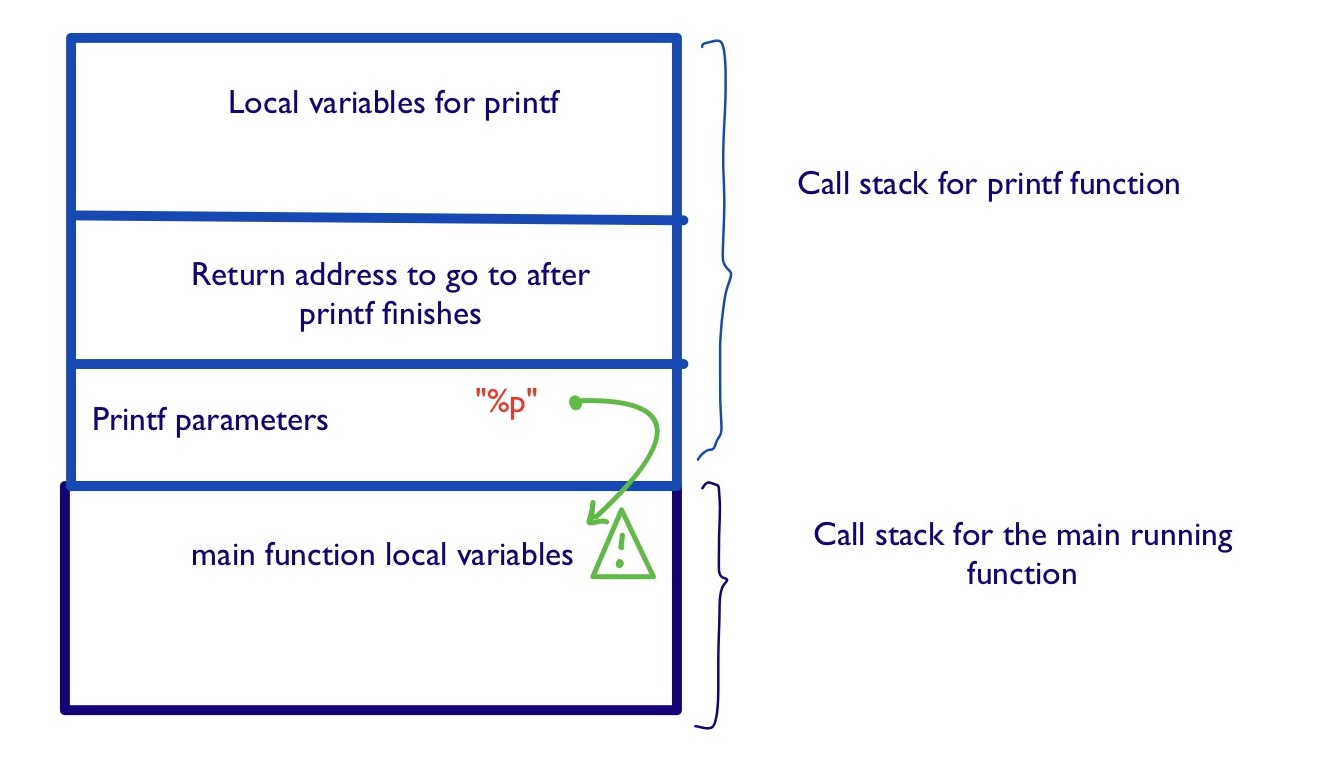

What is interesting is what happens when we forget to put the right amount of parameters according to the desired format string.

a_pointer int*

printf("%p")

In the code above, we do exactly this: the format string clearly seems to want a

pointer to be displayed, and this one should be the second parameter to

printf. This is the precise place where the function becomes unsecure: the

printf algorithm will still read whatever comes next on the stack and use

it as if it were the second parameter to printf.

The above picture represents what could happen. We now see how we could prepare a special format string that will read on the stack until it can find something interesting to show us.

Cooking a payload and pwning

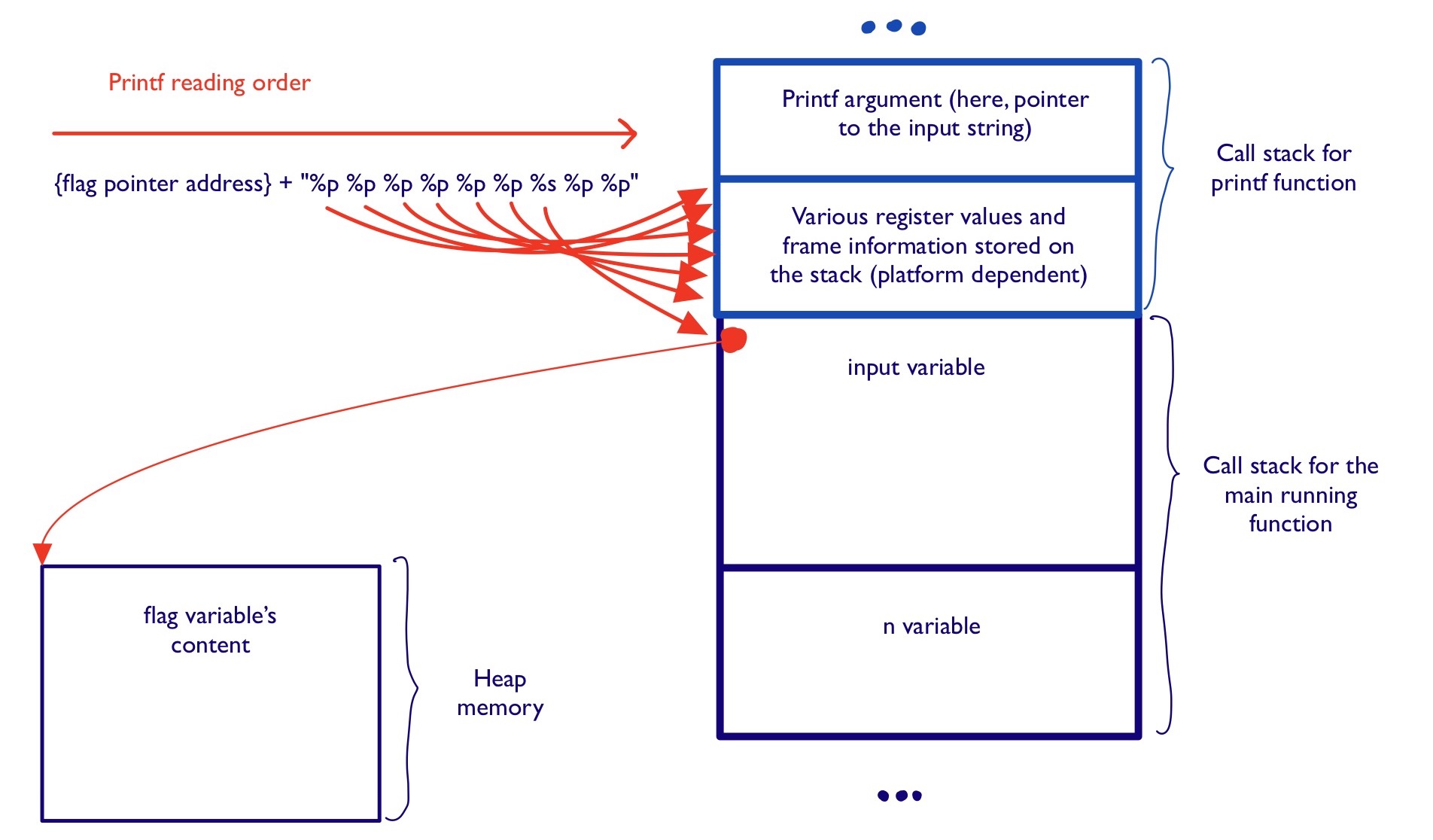

Long stories short, the payload that worked for me was:

{flag pointer address}+"%p %p %p %p %p %p %s %p %p"

Here’s how I understand why it worked: sending this value:

- Puts this string in the char array allocated on the stack of the main function.

- When

printfgets called, this string is read from left to right, and interprets each format specifier one after the other. - The first 6

%ptell theprintfalgorithm to look 6 bytes forward in the stack and display these bytes as a hexadecimal value. - After the 6th

%p, it seems that theprintfalgorithms looks at the beginning of theinputvalue to know how to replace the given%sspecifier. - Fortunately, we put the previously retrieved address of the

flagstring as the first value in input! Theprintfalgorithm therefore interprets this as “OK, this address is the address of a string I should print to replace this%sspecifier”, and gives us the content of theflagvariable.

You may wonder how I found that 6 %p were necessary: honestly I tried with 1,

2, 3, up to 6. This value depends on what is between the printf arguments in

the stack and the local variables of the main function. This value depends on

the platform and I did not want to look deep into this :).

The picture above tries to illustrate the flow we described that leads printf

to show us the content of the flag variable.

I hope this helped you to better understand how to perform this kind of attack and maybe solve your CTF. Let me know in case you would like more information or if something is not clear (see contact info on home page).